(This article was first published in the New Vision on September 7, 2022)

By Francis Emukule and Mary Karugaba

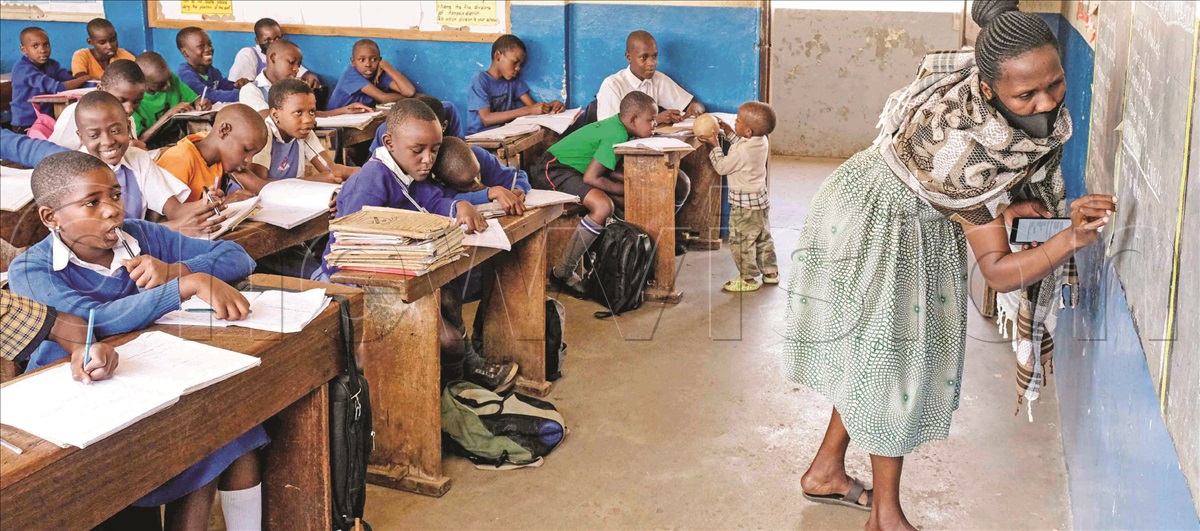

Priscilla Karungi, a resident of Nateete, a Kampala suburb, was invited to collect her 11-year-old son from school a week before August 12, when schools officially closed for holidays.

The school, located in Kampala, explained to Karungi that it was closing a week before the official date because of the increasing prices of food and scholastic materials, triggered by increasing fuel prices.

Karungi was then handed a circular saying the school had increased her son’s fees for the third term by sh200,000 to cater for the rising operational costs.

“The cost of living has gone up, but everyone is affected. There is need for parents and schools to find a win-win situation,” Karungi says.

Several schools have increased school dues this term, ignoring the education ministry’s warnings against the move, citing the increasing costs.

In a January 11 fees circular to public and private primary and secondary schools, for instance, the ministry acknowledged that schools had increased fees without its permission.

According to the ministry’s fees guidelines, proposed fees changes are supposed to be approved by the board of governors, school management committees and Parents-Teachers Associations, which have representations from parents.

Once the parents agree to the proposals, the school is expected to seek the ministry’s permission for implementation. But Karungi says her son’s school did not follow this process.

“I learnt from the circular that fees had been increased,” she adds.

To stop the public and private primary and secondary schools from further ignoring fees directives, the ministry is currently developing regulations to facilitate enforcement of the Education Act 2008, which gives the minister powers to regulate school charges.

Regulations Under Review

The proposed regulations are currently being reviewed by the justice and constitutional affairs ministry, according to the state minister for primary education, Joyce Kaducu.

Apart from the seed secondary schools, where learners do not pay fees, the proposals are expected to apply to two categories of schools; privately-owned ones and Government-aided schools founded by faith-based institutions.

The faith-based schools collect fees because the Government does not give them capitation grants to implement free education, but it gives them scholastic materials and also pays the salaries of the majority of their teachers.

But is state regulation of fees possible?

Godfrey Busobozi, the national chairman of the Coalition of Private Teachers’ Associations and Unions, says the proposal is unlikely to succeed.

“Many private school owners are Government bureaucrats. They seem to be supporting the proposal because that is the position of the Government,” he adds.

Busobozi explains that the structure of Uganda’s economy also makes it hard to regulate school charges.

“It can work where the state has a strong hand in the economy. Capitalist Governments like ours believe in sucking money from the rich and redistributing it to the poor,” he adds.

“You have to allow schools to charge what they want in a free market and impose taxes on them to redistribute wealth. Schools cannot thrive if they cannot motivate teachers.”

The failure to attract the best teachers and keep them motivated would lead to the collapse of teaching standards, according to Immaculate Lwanga, the headteacher of Trinity College Nabbingo, a government-aided school. She adds that in many cases, the fees rates are determined by the quality of teachers hired.

“It is good to protect parents from schools which overcharge, but this should not affect the quality of education,” Lwanga adds.

“The proposal is not bad because some schools have doubled fees, but commodity prices have also skyrocketed,”

According to information before Parliament’s education committee, some schools have increased fees by 50%.

Victoria Bagaya, a teacher at Mbale Senior Secondary School, a government institution, says, however, that the ministry should not base its regulation on parents’ sentiments.

“But schools which increase fees every term or year need to be checked,” she states.

Leonida Kababito, a teacher at Kawaruju Primary School, a Government school in Kyenjojo, says privately-owned schools should enjoy the freedom to determine fees in order to stay afloat as they are not state-funded.

Parents In Court

But it is not only Ugandan parents who have complained over school fees hikes in East Africa. In 2020, the Kenyan High Court dismissed a petition by parents who sought to compel the Government to enact a law to regulate the fees charged by local and international private schools.

In its ruling, the court said private schools are not financed by the taxpayer and should continue to determine fees based on the forces of demand and supply.

Although the Tanzania Government has previously directed private schools to submit their fees structures following complaints from parents over fee hikes, it announced this year that it would no longer require schools to do so.

Instead, the Tanzanian education, science and technology minister, Prof. Adolf Mkenda, told the media in May that the Government would instead improve the public schools to encourage parents to send their children to state-owned institutions. He reasoned that the state involvement in the determination of fees would negatively impact investment in a country seeking to attract more private players into the education sector.

In Rwanda, parents have over the years complained about the fees increment in private and some public schools. However, the Government has always encouraged schools to engage parents before revising fees.

All the three Governments have not yet made a direct intervention in the determination of fees. Will Uganda succeed in a territory where her neighbours are afraid to venture?

Long Overdue

Fagil Mandy, an educationist, says fees regulation is long overdue, and that there is “nothing” that cannot be controlled by the state.

“We cannot let a critical service like education be handled purely as a business. How schools are run and make profits must be controlled,” he adds.

Meanwhile, Fred Muhumuza, an economics lecturer at Makerere University, wonders how schools, which are not financed by Government, would adjust to varying economic conditions if the regulations introduce limits on fees increases.

But Mandy says this should not be a source of alarm.

“If you find it hard to run a school, go into other businesses,” he says.

“Government has to control the cost of education,”

An official at the ministry, who spoke to Mwalimu, but is not authorised to speak to the press, concurs with Mandy.

“Education is a service. It is not for people looking for profits,” he says, encouraging parents to report schools that have increased fees without permission.

“We cannot act if the parents have not reported to us,” the official said.

However, Peter Motovu, a parent, says the fact that the ministry plans to partly rely on parents to know schools which have flouted its regulations shows how complex implementing the fees controls would be.

Improve Public Schools

Anthony Okecho, another parent, who says he pays sh4.1m in school fees for his five children in private schools per term, thinks fees regulation is unnecessary.

“I pay sh2.3m for one child and the four take sh1.8m. Parents should make choices depending on the standards of schools,” he adds.

Abel Asiimwe, the proprietor of Mpumudde High School and Jabez Victory Nursery and Daycare School in Jinja City, says his school purchased 100kg of maize flour for sh160,000 before the start of the second term, but the same was going for sh300,000 by the end of the term.

“They should also regulate other items,” he adds.

Roger Andama, a parent who says he has a child at Gayaza High School, wants the Government to improve the teaching standards in private schools. This, Vanansio Natuhwera, also a parent, says will attract learners to public schools, hence compel the private ones to lower fees.

“Private schools are acting like this because there are no better alternatives. Honestly, Government schools are substandard,” he says.

While Karungi welcomes the idea of regulating fees, she is unsure how this would affect her son’s learning.

“Who will ensure my son is well-fed and taught?”