By Andrew Masinde

Emma Wamutinyi, 15, is both visually and physically impaired. He attends Makhonje Primary School in Mbale district in a wheelchair because he is hopeful that education could give him a better life in the future.

But a lack of learning aids for children with special needs at this school hinders the learning of this P5 pupil. For instance, the school lacks braille machines, slates, and styluses—which blind children use to write.

“I am faced with challenges such as braille papers,” he says. “I am lucky to have a teacher who helps me learn despite these challenges,”

To help him and other blind children learn, Wamutinyi says their teacher, who is also visually impaired, borrows learning tools from other schools. All 214 of the students with disabilities at this school struggle with a lack of learning materials.

Tim Wananda, 14, limps to school because one of his legs is crippled. His arm is crippled, too. Wananda, who is also a P5 pupil, relies on donors for learning materials such as books.

And once he uses up the books donated to him, Wananda, who lives with her grandmother three kilometres away from the school, does not take notes in the classroom.

“It is good to be at school because other children love me,” he says. “But the challenge is a lack of scholastic materials,”

Around 16% of Ugandan children have a disability, according to the World Bank. The education ministry says there are over 170,000 and 8,000 children with disabilities in primary and secondary schools, respectively, representing 2% and 0.6% of the total population of learners at these two levels of education.

The low enrollment of children with disabilities in school is due in part to a scarcity of special needs schools and learning materials.

Special needs schools

According to the education ministry, there are only 24 special needs schools in the country, and only 126 mainstream schools provide inclusive education (teaching children with and without disabilities together).

The Persons with Disabilities Act 2019 says any institution that admits a learner with a disability is required to provide inclusive education. It bars institutions from denying admission to a learner on the basis of a disability.

But the majority of mainstream schools do not have teachers and facilities to provide inclusive education, which partly prevents children with special needs from attending school, especially if the only institution closest to them cannot accommodate them.

Keeping children in school

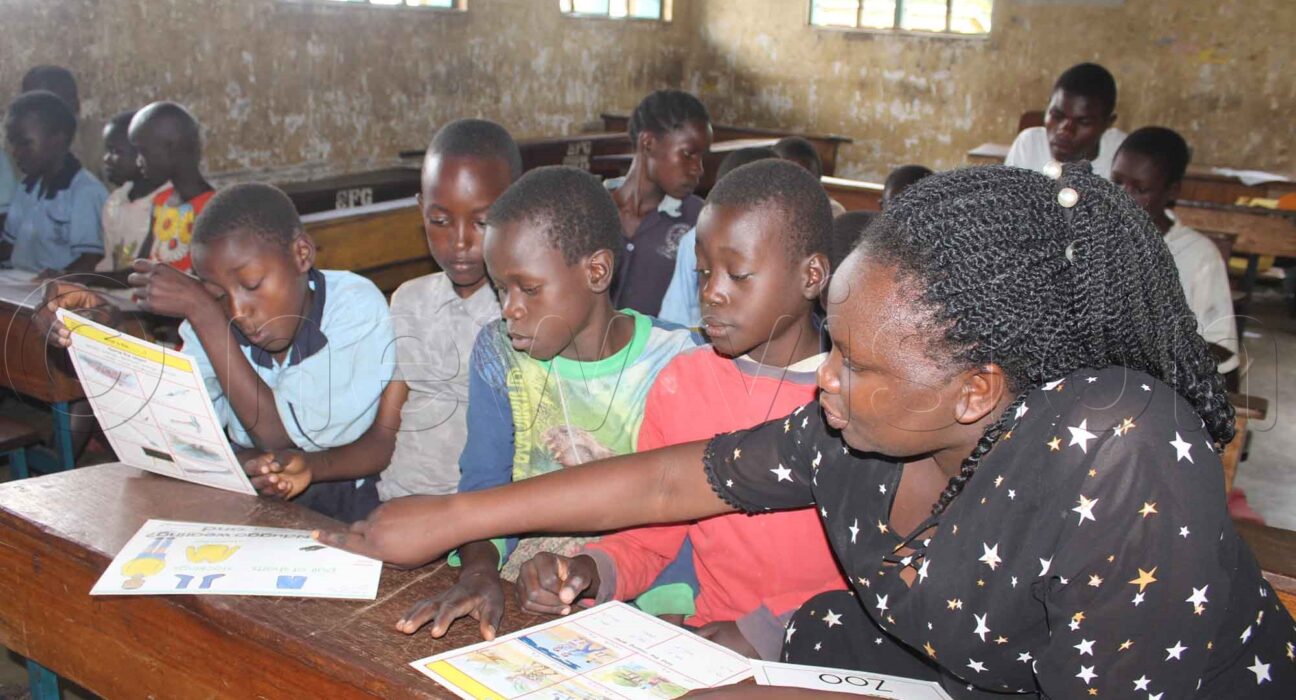

Juliet Walyamboka, a visually impaired teacher at Makhonje Primary School, says she lends special needs children the teaching aids she used while she was in primary school several years ago.

She adds that many children with special needs report to school without scholastic materials to aid their learning. This, Walyamboka says, does not only pose learning challenges for these children but also for the teachers.

“It is very hard for them (children with disabilities) to study together with non-disabled children because these two groups do not understand at the same pace,” she adds.

Beatrice Namuganza, who is also a special needs teacher at this school, says some families with children with disabilities are too poor to keep these learners in school. However, she notes that other parents do not value the education of children with disabilities.

“They come to school without books, pens, and pencils. The parents do not even find out how their children are doing at school,” she adds. “It’s like they just want to send them away from home. But our school puts aside little funds to support these children,”

Crying for attention

In a 2011 survey conducted by the African Child Policy Forum, the majority of Ugandan children with disabilities who were not in school over 11 years ago, said their caregivers prevented them from receiving an education.

The Genesis Education Centre in Mbale, which rehabilitates vulnerable children, says that on some occasions, children affected by albinism have been dumped at its offices.

Its director, Milly Nabalayo Buku, says the limited number of special needs teachers in schools not only impedes the education of children with disabilities but also exposes them to emotional abuse from people who are not trained to handle them.

Teddy Nambuya, a special needs teacher at Buwamwangu Primary School in Mbale, says some teachers who receive special needs education training do not teach, while others upgrade their education further and get promoted.

This, she adds, keeps children with special needs underserved in mainstream schools. But there is also another challenge. “Special needs education teachers are sometimes assigned to schools that do not have special needs units,” she adds. “Special needs children do not get the attention of teachers in many schools.”

Teaching materials

Lovenunce Lunyolo, the headteacher at Busiu Primary School in Mbale, says some of the mainstream schools do not receive special funds to educate children with special needs. Only schools with special needs units receive teaching materials to take care of children with disabilities.

For instance, in Kagadi district, only Bishop Rwakaikara Primary School has a special needs unit. As a result, according to Lunyolo, many mainstream schools rely on capitation grants to educate special needs children and learners without disabilities.

For each child under the universal primary education programme, the government provides schools with around sh10,000 per term. “This money is not enough for schools to buy things like braille papers for special needs children,” Lunyolo says. “My school (mainstream school) has 53 pupils with disabilities, yet we don’t have special needs teachers. We work with existing teachers and they try out sign language, which disrupts learners,”

John Paul Kodet, the Napak district chairman, says local governments do not raise enough revenue to procure learning materials for children with special needs.

Getting to school

However, Anna Lomonyang, the founder of the Rural Disabled Persons Organisation of Moroto, says special needs children not only lack learning materials but also assistive devices like wheelchairs, white canes, hearing aids, and crutches to travel to school.

“These devices are expensive, and many poor parents cannot afford them. Many don’t send them to school, and some of these children drop out of school. Those who complete primary cannot join secondary because of these challenges,” she adds. “Poor sanitation and stigma force some to drop out,”

That is part of the reason children with special needs constitute the largest group among minority learners who fail to complete primary, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Robert Simiyu Chemuku, a teacher at Longlalom Primary School in Napak says schools could establish special funds to care for children with special needs.

Joyce Nakoya, the Napak district education officer, says a change in parents’ attitudes and their support for the education of special needs children could get many of these youngsters to school.

Skilling children

Sarah Ayesiga, the assistant commissioner for inclusive and non-formal education at the education ministry, says that nowadays teachers are given basic skills for handling children with special needs in teacher training colleges.

She adds that special needs education will soon be “vocationalised” to skill children with disabilities. “This will help learners with disabilities earn vocational skills, for instance in carpentry and joinery, cooking, tailoring, and many others,” Ayesiga adds.

However, she notes that a lack of facilities and specialisation in special needs education as well as low digital literacy levels among tutors still hinder the delivery of inclusive education.

Ayesiga agrees that the cost of special needs education materials remains prohibitive for some parents as the Government strives to find more resources to fund education.

Wamutinyi is concerned that if a teacher who provides him with learning materials is transferred, he will join the ranks of special needs children who drop out before finishing primary school. “If she gets transferred, I will never get these materials again,” he says.