(This article was first published in the New Vision on November 23, 2022)

By Ibrahim Ruweza

When Allen Mutatiina enrolled her three-year-old daughter Precious Nimusiima in a nursery school in 2006, she did not know that her child was not equipped for the daily routine of waking up before 6:00am to prepare and for school.

For a couple of weeks, Mutatiina woke Nimusiima up at 5:30am. But as she bathed and dressed her up, the girl closed and rubbed her sleepy eyes. Occasionally, she went back to bed as the school van made its way to her home. And as Mutatiina escorted her sleepy daughter to the van, which arrived at their home in Seeta, Mukono district at 6:00am to pick her up daily, Nimusiima would cry.

“She showed me she was not ready to leave home. Later, I allowed my daughter to sleep up to 8:30am,” she says. Mutatiina and her husband asked the school to stop sending the van to pick up their daughter and decided to take her by themselves to this institution located in Bweyogerere, Wakiso district, about 8km away from their home.

“The teachers thought we were pampering our girl. I told them ‘It’s okay’. We were like rebels,” she says.

Mutatiina, who describes herself as a marriage counsellor, says this reminded her of the need to spare children the rigours of a competitive school system and considered homeschooling.

“I realised our education system was teacher-centred and learners crammed what the teacher gave them to pass exams. The teachers even wanted our daughter to skip Top Class and go to Primary One, saying she was bright and would waste time in Top Class, but we refused,” she says.

“Education is not about passing exams. We wanted her to go through all the stages,” Mutatiina adds.

How It Started

While in Top Class, Nimusiima started returning home with homework and holiday assignments. Her parents told the school she would not do any assignments at home before she reached Primary Two.

“Holidays are for bonding, doing house chores, playing and engaging with the world around her,” Mutatiina says.

In 2010, when Nimusiima had reached Primary Three, the couple started homeschooling her. According to a 1992 study published in the American Journal of Education, homeschooling gained momentum after the education reformists of the 1960s and 1970s attacked the quality of public education. It is now recognised as an alternative educational option in various countries, including the US and the UK.

Over the years, several curricula have been developed to facilitate homeschooling. For their daughter, Mutatiina and her husband chose the Christian Liberty School Systems curriculum developed in the US. This year, Nimusiima completed Grade 12 – an equivalent of Senior Six under the Ugandan education system.

If she chooses to join a university in Uganda, all she would have to do is to request the Uganda National Examinations Board to convert her results into Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) and give her a certificate. She can also join a university as an international student without a UACE certificate.

But how did this couple instruct Nimusiima and their son, who recently completed the Ugandan Senior Three equivalent? Mutatiina says the curriculum developers in the US sell her packages for each grade or class and that the curriculum is “straightforward”.

“My children know how to look for learning materials and tutorials and contact the curriculum developers with questions. You don’t need to be a teacher to guide them,” she says.

But whenever her children needed help, she could not offer it and could not get it online, so she engaged Ugandan teachers to teach her occasionally.

“I engaged a fine art teacher and another for science practical lessons,” Mutatiina adds.

Child Development

Agatha Kisakye Kabugo and her husband Martin Kabugo have homeschooled their 13-year-old boy, Jethro Kisakye and 11-year-old daughter Keziah Kisakye at their home in Kanyanya in Kampala for eight years, also under the Christian Liberty School Systems curriculum.

Kabugo, a social worker and her husband, an IT specialist, started homeschooling their two children after they had both gone through kindergarten. Jethro and Keziah are now in Grade Six and Grade Four respectively – the equivalent of Primary Seven and Five under the Ugandan curriculum.

Kabugo says they removed their children from a mainstream school after learning that the teachers’ focus was on completing the syllabi rather than developing the children’s individual abilities.

“The teachers were appraised in terms of how much of the curriculum they had covered,” she adds.

The schools’ practice of splitting the children of the same class into streams on the basis of their level of comprehension or intelligence as defined by the schools made her further detest the traditional schooling system.

“The children placed in the streams meant for those who are deemed not bright know they are not good. All children are good at something, but the traditional system cannot get such a thing out of a child,” she adds.

Kabugo says Jethro is now a writer and has produced two fictional books for children and is writing a third one for teenagers. Keziah makes jewellery and is building a brand for it.

“Parenting cannot be delegated or postponed and parents operate within a window of time. Once it closes, you cannot change anything,” Kabugo adds.

However, parents can also attach their homeschoolers to private schools that implement the Ugandan curriculum or international schools in Uganda.

Catherine Ahumuza, who is homeschooling 20 children, including two of her own in Muyenga, a suburb of Kampala, has attached her homeschoolers to Kansanga Parent’s Primary School, where they sit their end-ofterm and Uganda national exams. Ahumuza, who taught at one of the international schools around Kampala, chose to homeschool her two children in 2013.

“Friends and neighbours brought their children to me after learning I was homeschooling mine,” she says.

Ahumuza says it is cheaper to implement the Ugandan curriculum than international curricula like Christian Liberty School Systems and the Accelerated Christian Education as these involve buying all the content.

More Care Than Teaching

Didian Mukunde, who started homeschooling her two children during the COVID-19 period, says home-based learning gives parents an opportunity to give their children more care than they get at school.

“Children need more care than learning. Too much academic content at a younger age can affect a child’s academics in the future, leading to poor performance and dropout,” she says.

However, a specialist in behavioural science and neural studies, who preferred to remain anonymous, says some parents doing homeschooling “impose their career desires” on children. This, he says, denies the children the chance to make independent career choices.

“These children are denied an opportunity to engage fully with their communities because they do not attend school. They sometimes become prisoners of reading, writing, arithmetic and the Bible,” he adds. “They grow up with parents’ ideas and have no other perspectives.”

However, Mutatiina, Ahumuza and Kabugo say they create opportunities for homeschoolers to interact with traditionally schooled children through co-curricular activities such as music concerts and sports.

“My children break off for holidays at the same time as the children in Ugandan schools, so they have an opportunity to meet with children in our neighbourhood,” Mutatiina adds.

Statistics

The Home Schoolers Uganda Group executive director, Godfrey Kyazze, told the Education Review Commission that 1,700 Ugandan children are currently being homeschooled in about 600 homes.

What Education Ministry Says

Ketty Lamaro, the education ministry permanent secretary, says while homeschooling is developing in Uganda, she does not know of any previous efforts to get it recognised.

“I am not aware of any policy or guidelines about it,” she says.

While advocates of homeschooling have discussed its benefits extensively, studies published in respected and peer-reviewed journals such as American Journal of Education show that parents carrying out homeschooling replicate elements of public education. This, according to these studies, means the benefits reaped by homeschoolers are available to children in mainstream schools, too.

But a 1992 study published in the American Journal of Education says the typical parent-teachers in home schools are middle class people with several years of education, while a 2012 survey available in the International Social Science Review notes that “homeschooling is not for everyone”, and not every family can effectively home-school children. “Do not home-school your children because others are doing it. It is a sacrifice,” Kisakye says.

Holistic Learning

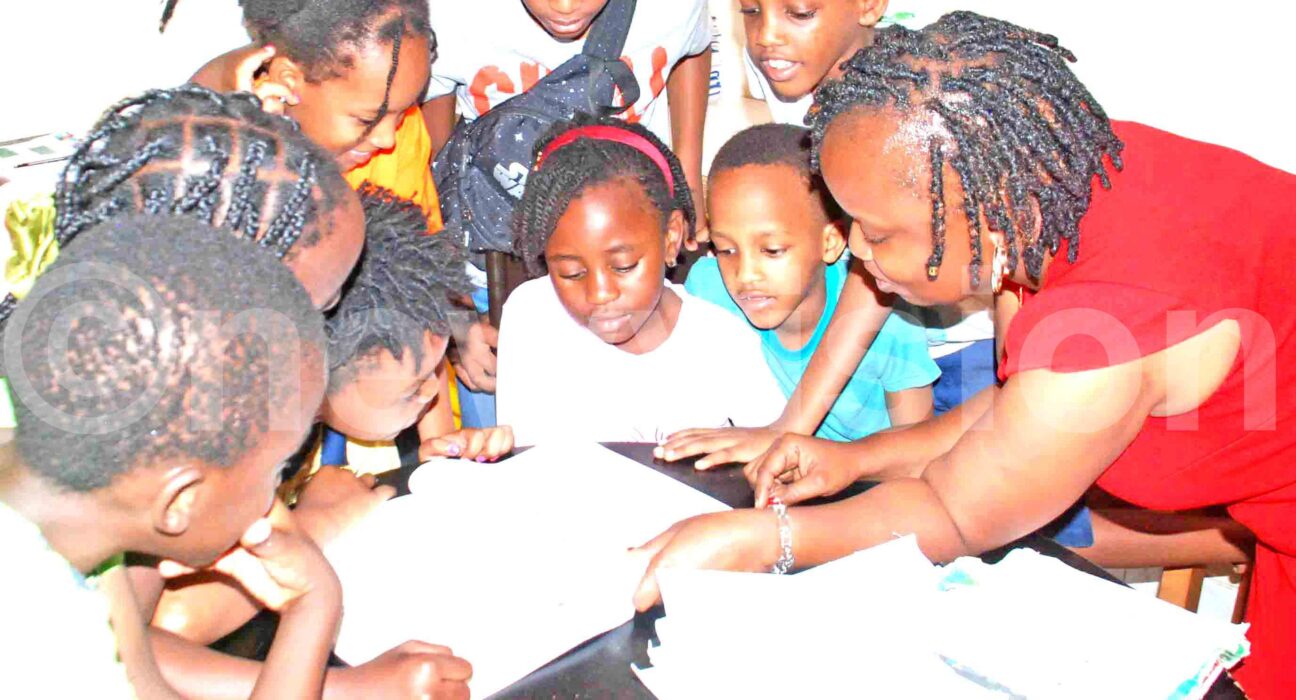

Shalom Kirabo, 11, one of the children Ahumuza has been teaching, sat her Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) at Kansanga Parent’s Primary School this month. When Kirabo returned to her home school after writing her last PLE paper on November 9, she was congratulated and hugged by about 10 children.

“I have done it. I am going to pass,” Kirabo said as she approached her teacher after hugging her fellow children. Kirabo says studying in a home environment allowed her to learn vital life skills.

“It has not just been about academics. I have learnt how to cook, table manners, self-control, and computer applications,” she adds.

Chance James, a teacher at Kansanga Parents’ Primary School, says Kirabo has been taking the same promotional exams as other children.

“We currently have 11 homeschooled children attached to our school. These children do not pay school fees because we do not teach them. But there are small bills for things like scholastic materials which are handled by teachers or parents,” he says.

Ahumuza says she teaches the children all the subjects, but, after every two weeks, she invites teachers from other schools to instruct the learners and assess their progress.

Kyazze, a lecturer at Uganda Christian University, says he home-schools his children.

“My first-born recently completed Primary Seven and I home-schooled him. I am home-schooling all my children because I want them to develop the way I want,” he adds.

However, Anthony Mwesigwa, who has taught in public and home-schools, says homeschoolers are sometimes compelled to “specialise at an early age and this denies them an opportunity to get more perspectives about the world”.

“All they know sometimes is what the mother and father taught them,” he adds.

But Belinda Gasana, a parent, who has also homeschooled some of her children, says home-based education engages parents in their children’s learning and helps them understand their unique gifts. This, she adds, allows teachers to develop content tailored to the children’s desires.

Homeschooling Group Speaks Out

Last month, Home Schoolers Uganda Group (HUG) presented a petition before the ongoing Education Review Commission asking the Government to recognise homeschooling – which is still new in Uganda – as one of the educational options.

The HUG executive director, Godfrey Kyazze, told the commission that 1,700 Ugandan children are currently being home-schooled in about 600 homes.

The Government’s recognition of homeschooling, Kyazze said, would allow more parents to educate their children at home. It would also allow homeschoolers to take exams at public schools.

“It’s not expensive because parents are involved in teaching, but those who have no time might be paying professional teachers sh1.3m to homeschool a child per term,” he said.

Pros

Home-based learning gives parents an opportunity to give their children more care than they get at school.

Cons

Children do not get an opportunity to interact with others since they do not go to school.

Advice

Parents are advised to engage professional teachers whenever they need help.