(This article was first published in the New Vision on 18 August, 2021)

As you think of your child’s start of schooling in Senior One or Senior Five, do not forget to pay attention to the cost you are likely to incur, writes Conan Businge

It is a fact that early care and education, in certain instances, costs higher than some primary and secondary schools. The days when nursery schools only cost a few tens of thousands, are long gone. Today, even the kindergarten next door charges hundreds of thousands at the very least.

The ever-increasing cost of living has not spared kindergarten education. Several nursery schools have had to adjust their charges upwards to break even The school fees paid at today’s nursery schools vary, depending on the location, facilities, human resource, ownership and the services offered. Since there are no government-aided nursery schools, the cost of nursery schools is too high.

Several parents have opted to sell off their property to educate their children in good schools. Some pupils drop out or never step in school because of poverty.

Much as there is no guaranteed return on investment to parents, World Bank studies show that education might help their children participate in the labour market, experience less unemployment and, or attain higher skills, which in turn improve their chances of getting a better pay than those that are not educated.

Justification For Spending

But why would parents spend so much on their children’s education? In a 2015 report by researchers at Makerere University and the education ministry The Future Schooling in Uganda, the researchers note that in Uganda, investment in education has been prioritised in the last two decades because it is hoped to facilitate reform in other sectors after a long period of civil strife.

Education is expected to contribute to the accumulation of human capital, which is essential for higher incomes and sustained income growth.

“There has been extensive expansion of the education system in order to make it accessible to the larger population,” it adds.

With the introduction of Universal Primary Education in 1997, and with the introduction of Universal Secondary Education in 2007, it is hoped that the majority of the children in Uganda will be able to access the full cycle of primary and secondary education.

This is a huge investment as education is linked to children’s survival and secondary education is associated with smaller family size.

Goal 4 of the Sustainable Developments Goals calls for inclusive and quality education for all and to promote lifelong learning. But, poverty limits the chances of educational attainment, and, at the same time, educational attainment is one of the prime mechanisms for escaping poverty. Poverty is a persistent problem throughout the world and has deleterious impacts on almost all aspects of family life and outcomes for children.

Much as the Government allocates 14% of its total budget to funding education, the 2016 National Education Accounts (NEA) report shows that the highest burden of education in Uganda is being borne by households — parents.

The NEA report was done by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and the education ministry, supported by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

In 2014, education was funded by households (47.23%), the Government (27.21%) and development partners (24.65%), up from 6.05% in the previous year.

The same report shows that most of the funds from the Government go to paying salaries and administrative costs.

“In 2014, 38% of education ministry’s expenditure was allocated to salaries and 41% to the other running cost of the central administration,” reads the report.

The households’ expenditure on education, “is more than what is officially believed to be” says the NEA report.

“A lot of information on household expenditure goes unrecorded and yet the household expenditure contribution to the sector is highly significant,” it adds.

Government studies show that with fees averaging $450 (about sh1.58m) per year in primary and secondary schools, many families simply cannot afford to send their children to school.

In addition, UBOS reports show that only 40% of villages in Uganda have a secondary school. Therefore, for many children without any means of transport, school is just too far away.

The gross domestic product per capita in Uganda is just at an all-time high of $673.21 (about sh2.37m), having averaged at $432.80 (about sh1.5m) from 1982 until 2015. This means, that the families spend almost all their earning on school fees.

Higher education state minister Dr John Muyingo says the Government has tried to invest in more public universities as a way of having cheap, but quality higher education. In a period of two years, three more universities have been set up, to support the other six public universities.

“Knowing that the cost of education was also high, we started free primary and secondary education, on top of scholarships and grants in institutions of higher learning,” he says.

Much as there is Universal Secondary Education (USE), parents still have to part with money to get other scholastic items. However, several high schools charge fees which are higher, or equal to those, paid at universities.

This is one of the reasons why only 23% of boys and 19% of girls complete lower secondary school.

If a family does not have enough money to send all their children to school, they are more likely to send boys and keep girls home. This is likely as a result of the perception that boys have greater earning potential, and girls are often kept at home to help with household duties.

To make matters worse, only 5% of the boys and 4% of girls progress to tertiary education.

Is Uganda Alone?

In all countries, studies show, poverty presents a chronic stress for children and families that may interfere with successful adjustment to developmental tasks, including school achievement.

Children raised in low-income families are at the risk of academic and social challenges, as well as poor health and well-being, which can, in turn, undermine educational achievement.

The Africa Learning Barometer, produced by the Brookings Centre for Universal Education, indicates that only about half of the sub-Saharan Africa’s 128 million school-aged children, currently attending school, are likely to acquire the basic skills needed for them to live healthy and productive lives.

The centre’s research further suggests that if you are a poor, female child currently attending school in a rural region, you are far more likely to not be learning the critical skills, such as reading, writing and math. While these gender, income and regional learning gaps exist in most sub-Saharan African countries, they are most salient in South Africa, Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Botswana, due to the policy implementation challenges.

According to the 2016 poverty assessment by the World Bank, Uganda has reduced monetary poverty at a rapid rate. The proportion of the Ugandan population living below the national poverty line declined from 31.1% in 2006 to 19.7% in 2013; due to increasing entrepreneurship and agricultural growth in the country.

The same report notes that the country was one of the fastest in the sub-Saharan Africa to reduce the share of its population living on $1.90 purchasing power parity per day or less, from 53.2% in 2006 to 34.6% in 2013. Nonetheless, the country is lagging behind in several important non-monetary areas, notably improved sanitation, access to electricity, education (completion and progression) and child malnutrition.

High Dependency Ratio

As parents are struggling with high fees, the country’s dependency ratio is growing and largely lying among the age of school-going youths and children who don’t earn a living. This means that parents or families will still have to bear the growing cost of education, since economic growth is not well-spread among the population.

The latest Uganda Bureau of Statistics National Census report shows that the age dependency ratio (percentage of working-age population) is now at 103%. Age-dependency ratio is an indicator of the economic burden that the productive population must bear.

Populations with high birth rates, coupled with low death rates, have a high age dependency ratio. Overall, the age dependency ratio is 103. This implies that for every 100 economically active persons, there are 103 dependants. The dependency ratio active age is higher for males (110) than for females (97). This implies that if individuals have more dependants, there will be little disposable or saved money that they can use to invest in personal economic development; which is later reflected in economic deployment of the nation. In most homes, the biggest expenditure goes to health and education.

However, students, according to the 2016 National Education Accounts (NEA) report, constitute only 32.9% of the country’s population. If those below 18 years are 55% of the entire population, it means that about 18% of the young ones are not in school.

Since parents have to look for money to keep their children in school, in some instances, parents are marrying off their children at an early age. At times, some parents withdraw their children from school to work on farms, to raise more money to sustain their homes.

“Gradually, when poverty kicks in and there are so many dependants, education ceases to be a priority for many families” Sam Opolot, a former local council leader in Soroti district, says.

“Some of us spend most of our money educating our children. Just imagine if a parent saved all the money spent on a given child’s education, how much more would such a parent do with it,” Dennis Mulindwa, a parent with four children in secondary school, says.

Some educationists, experts and parents say there is need to continue with more poverty eradication programmes in the country.

Some children are forced to drop out of even free government-aided schools because of failure of their parents to provide basic learners’ needs, such as books, pencils and pens

Public Versus Private Education

Former commissioner for secondary schools at the education ministry John Agaba says the hidden costs in universal primary and secondary education schools, and the direct costs in private schools, coupled with poverty in the country, have robbed so many children of the chances of going to school.

Agaba proposes that the Government tightly inspects free primary education fees policy. This is on top of improving public schools to offer parents an alternative to expensive private schools.

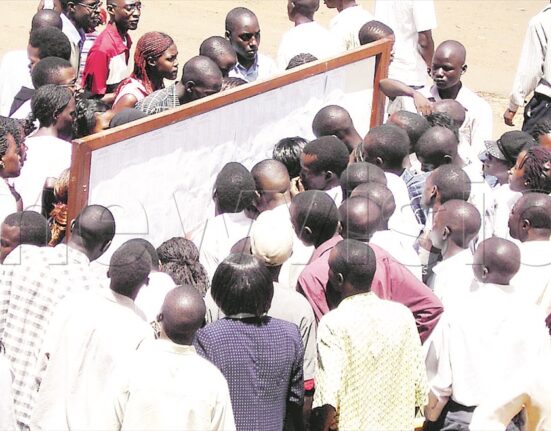

Indeed, Agaba has a point. As of today, after the high dropout rate in primary schools, the transition to Senior One is also low. Several children fail to sit for national examinations, partly due to the inability to pay for examination fees and other related hidden costs in public and private schools.

Peter Tusubira, a retired teacher, proposes that government invests in more public technical and vocational institutions.

“They can also support the private universities and institutions, through a public-private partnership arrangement, to make higher education more affordable and of higher quality.”

Even the public schools in the country are equally expensive. A parent has to part with sh800,000-sh1.3m on school fees per term for their child to study in a top public school in Uganda.

The Future Schooling in Uganda report notes that access to education can be improved by the continued provision of schools and classroom facilities, training teachers in special needs education, and provision of basic education in emergency situations.

There is also the need for expansion of vocational training institutions in order to address the needs of children who, due to some circumstances, completion of formal education cycle has been elusive.

Higher education state minister Dr John Muyingo also confirms the report’s analysis that the government’s focus for the next few decades is expected to be on maximising the impact of public expenditure by focusing resources on those who would not otherwise access education, as well as failed to access secondary and tertiary education, where universal access is yet to be achieved.

Uganda’s Poverty Eradication Action Plan projects says that in the next few decades, the Government will take measures to improve the efficiency of primary education, including multi-grade teaching, double-shift teaching and incentives for teachers in hard-to reach areas.

Quality will be improved by teacher training, implementing the use of mother tongue in lower grades and increasing the relevance of the curriculum.

Leave feedback about this