This article was first published in the New Vision on December 21, 2022

By Andrew Masinde

A path that leads to Namalu Mixed Primary School in Nakapiripirit district, Karamoja sub-region, runs beside clusters of ramshackle houses. These decrepit structures inhabited by several families here are built close to one another, making this place near the school look like a refugee settlement.

The place is filled with groups of men and women, each drinking a local brew called kutu kutu from a calabash. As you walk past these groups of people clustered around their old houses in Namalu town council, you are greeted by a seemingly well-maintained chain-link fence, giving an impression of a rosy picture inside.

Alas, beyond the fence lies a kitchen which has been converted into an accommodation facility for teachers. Next to it is another building which was built for two teachers, but its rooms have since been partitioned to accommodate seven instructors.

Past these two structures, right in the middle of the school compound, lies a structure built with thick metal sheets like the materials used to build houses locally known as maama ingia pole for Police officers and their families in the barracks.

Constructed in 2000, this structure currently accommodates 247 P1 pupils at a school with a population of 1,300 children.

Its windows are broken and held in place by logs. Its floor is dusty.

A teacher, who asked to remain anonymous, said this structure was set up on the school’s land to house children uprooted from their homes by cattle rustling, but was later converted into a classroom to accommodate the rising pupil numbers.

“It always gets hot (inside the building) but learning has to take place. It gets noisy from raindrops falling on the roof and teaching is suspended until it stops raining,” he adds

Leaky & Cracked Classrooms

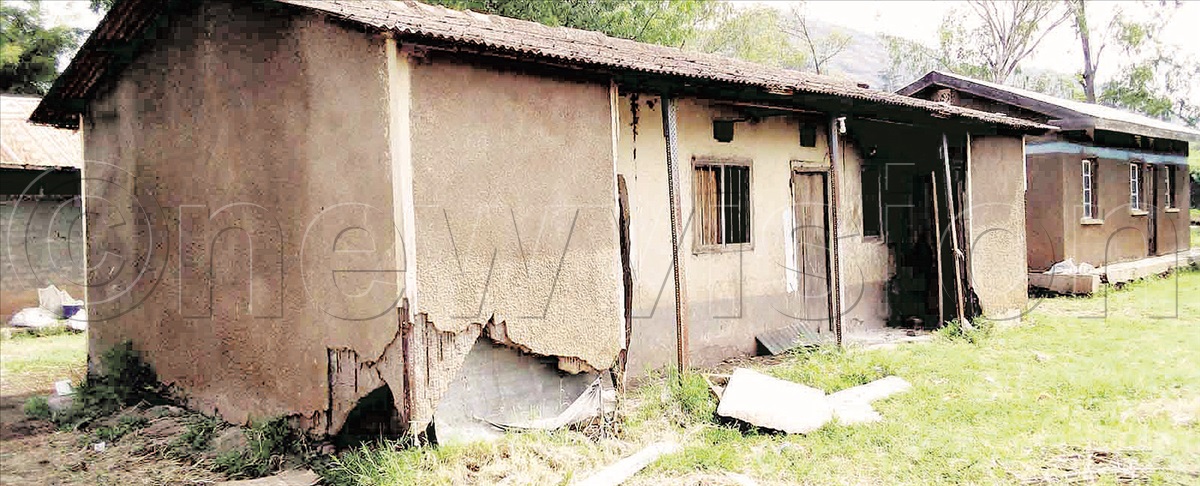

Close to this structure is a three-classroom block with cracked walls, rusty windows, doors and iron sheets. Its floor is dusty and the veranda is cracked. Not far away, there is a two-classroom block, also with cracked walls.

The gaping cracks have disintegrated its walls in some parts, which means the building could collapse anytime. When you are inside this building you can look outside through some of its cracks. The termites have been eating away its roof, which now hangs precariously over this weak structure. In addition, its roof leaks in the rain.

Innocent Masanja, a teacher, says each of the classes accommodated in this building comprises over 120 pupils.

“Even we as teachers know we are putting the pupils’ lives and ours in danger, but we have nothing to do. Where do you expect us to teach from? We hope the Government will come to our rescue,” he adds.

Jonathan Kodet, a pupil, says the leaky and dusty floors of the classrooms make learning hard. When it rains, he adds, pupils, who sit on the floors, have to huddle in some of the corners of these buildings to avoid getting soaked.

“Sometimes, the teachers send us home before it starts raining heavily. I think they do this because they think the walls of these buildings may collapse and hit us,” Kodet says.

Nowhere To Go

Inside the administration block, the cracks in the walls run from the foundation bed towards the roof. Like other buildings, the gaping cracks in the walls of the administration block are gradually splitting the (walls). Even inside this building, you can peep outside through the cracks.

The deputy headteacher, Geoffrey Owiny, says he has brought the school’s current state to the attention of the district and town council education authorities.

“We have nowhere to relocate the pupils to. The same applies to the teachers. We have covered the cracks and the dilapidated walls with manila papers,” he adds.

He confirms that the school sends the children home before its starts raining heavily to protect them from possible dangers. The teachers, too, have to move between the leaky rooms in the rain to avoid getting wet. This kind of situation, which is not unique to this school, Owiny says is part of the reason schools in Karamoja underperform.

“You cannot expect a teacher or a pupil or the headteacher to be comfortable working in these structures. We are always worried about what might happen next in case of strong wind and heavy rains,” he adds.

Broken Teacher Houses

Away from the classrooms and administration blocks, parts of the walls of the staff houses have collapsed. The teachers use old iron sheets and polythene bags to cover the holes in the walls. Their roofing materials contain asbestos, which is linked to various cancers in humans, according to the World Health Organisation.

The Parliament has previously directed educational institutions to get rid of roofing material containing asbestos to protect humans from health hazards linked to these minerals, which were in the past used in commercial products, such as roofing materials to protect from corrosion and heat.

If you breathe in air filled with asbestos fibres, these hazardous elements get trapped in key organs such as the lungs, causing cancers. Like the classroom and the administration blocks, the floors in the teachers’ houses, which were previously covered with concrete, are now bare-earth floors.

Snakes In Teacher Houses

A teacher said she previously found a snake in her house.

“I made an alarm and other teachers came to my rescue and killed the snake. It took three weeks for me to believe there were no other snakes in the house.” She adds.

“From that point, I bought old iron sheets to cover a big hole in the wall.

The snake entered the house through one of these holes in the walls,”

She urges the education authorities to at least repair their houses if there is no plan to build for the teachers new structures.

“Teachers in Karamoja also need to work in good conditions. We need to also be prioritised if we are to also catch up with the rest of the schools,” the teacher says.

Some of the pit latrines at the school have collapsed while the ones, which are currently used by the teachers and pupils, are on the verge of collapsing.

The Rev. John Baptist Aleper, the chairperson school management committee, asks the Government to put in a place a plan to rebuild the school to prevent a catastrophe from happening.”

Parents Concerned

Sarah Adimo, a parent, says she is worried that the school’s buildings could collapse and hurt her children.

“Part of the reason some Karamojongs do not educate their children is the poor state of schools. Our children study in cracked, dusty and old buildings,” she adds.

However, not all schools in Karamoja are in this state. The Government and development partners have over the years established schools in this northeastern part of the country. For instance, in 2016, the Government and its Irish counterpart commissioned 21 schools under the Karamoja Primary Education Project.

However, despite such interventions, there are still areas, such as Namalu, which are undeserved in one of the poorest regions in the country.

A highly placed source in the education ministry declined to discuss the state of this school and referred us to the district education authorities.

The Nakapiripirit district inspector of schools, William Abura, says there are 14 schools in a similar state.

He explains that the capitation grant allocated to these schools is not enough to finance their day-to-day operations and infrastructural development.

As Abura says it might take longer for the school and district authorities to realise enough funds to rebuild all the dilapidated schools.

Unless a special reconstruction plan is put in place, Namalu and other schools might have to wait a little longer before they get rebuilt.

Leave feedback about this