This article was first published on the New Vision website on April 26, 2023

By Charles Etukuri and Pascal Kwesiga

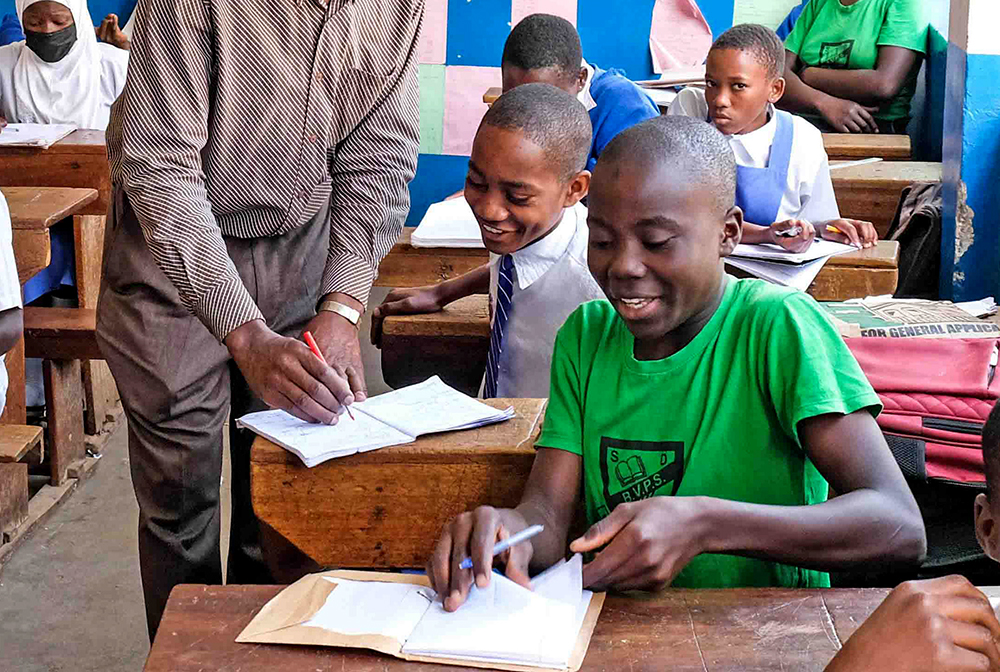

When Phyllis Nambuva started her schooling journey at Buhugu Primary School in Sironko district in 2016, there were 151 pupils in her primary one class.

But some of her classmates did not progress with her to Primary Two and Three over the two years that followed. Nambuva noticed that the number of her classmates reduced sharply as she progressed to the upper classes. Her peers were not repeating classes but were dropping out of school.

By 2022, when Nambuva wrote her Primary Leaving Exams (PLE), nearly half of the pupils with whom she started school, seven years earlier, had dropped out.

“Some of my colleagues, especially the females got married while some boys left school to find jobs to look after their families,” Nambuva says.

This high dropout rate recorded at Buhugu Primary School over a seven-year period is also experienced at other primary schools, especially universal primary education (UPE)ones.

Every year, nearly two million children begin primary school, but less than half and only slightly more than a quarter of this number in some cases complete primary. Pupils drop out of school at different classes, including some leaving as soon as they reach primary seven.

For instance, in 2016, over 1.8m entered primary one, according to the 2016 education statistical abstract. However, over one million of these pupils dropped out before completing primary as only over 830,000 of them wrote Primary Leaving Exams (PLE) in 2022 (see graphic).

But 2022 PLE candidature included pupils who were unable to write their exams in 2021 when schools were closed to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The pupils who were supposed to sit for PLE in 2021 were over 1.8m in Primary One in 2015. This means over 3.2m children were in Primary One in 2015 and 2016, but only over 830,000 of them wrote PLE.

The over 740,000 candidates who wrote PLE in 2020 were part of the roughly two million children Primary One pupils in 2014. There were over 1.8m in Primary One in 2013, and nearly 700,000 of them did PLE in 2019. In 2012, over 1.8m children entered primary, but just over 670,000 of them did PLE in 2018.

In addition, 1.8m children started primary in 2011, however, only over 640,000 sat for PLE in 2017. In 2010, close to two million children started primary, but just over 630,000 wrote PLE in 2016.

An analysis of the education abstracts and PLE candidate figures published by Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB) over the past seven years shows that 1.2m children out of the nearly two million who start primary each year drop out before reaching primary seven. Think of it as 800 schools, each with 1500 students, closing down each year.

Over the past seven years, the education abstracts show, there were close to two million children in primary one each year, but this number fell drastically as children moved to the upper classes. In some cases, the enrolment falls dramatically at Primary Two.

For instance, while there were around 1.9m children in Primary One in 2015, just 1.3m pupils were in Primary Two in 2016. This means around 600,000 pupils left school after or before completing Primary One in 2015.

The analysis shows that the enrolment remains stable at around 1.3m children between Primary Two and Four before it collapses to a million or below at Primary Five.

A similar drop is witnessed between Primary Five and Six, lowering the number of PLE candidates to between 600,000 and 700,000. Over these seven years, roughly 150,000 and 200,000 PLE candidates came from private schools. Since parents who enrol children in private schools have the means to keep their children in school, the majority of the children who drop out before PLE are in free government primary schools.

While it might be argued that a child might drop out after Primary One, for instance, and rejoin school in a different class later, the statistics do not show an increase in enrolment after Primary One.

Muhammad Maganda, who dropped out of school before completing Primary Six in 2021, is now a casual worker on sugarcane farms in Busoga region. “My parents did not have money to pay for my lunch at school, and when COVID-19 broke out, I started cutting cane and dropped out of school,” he says.

Poverty

The Minister of Education and Sports, Mrs Janet Museveni, who is also the First Lady, said the ministry is concerned about the low rate of primary school completion – which the ministry puts at 32%.

“I appeal to you all to note that completion of the learner’s education cycle should be considered a priority and a collective effort of the schools, parents and guardians, as well as the community in general,” she said at the release of the 2022 PLE on January 27.

She asked the educational authorities in the local governments to investigate the causes of the school dropout, adding that the ministry would also seek solutions to this problem.

A 2014 study led by Christine Mbabazi, a lecturer in religious studies in the department of religion and peace studies at Makerere University, cited financial constraints as the most prominent factor responsible for high drop-out rates and non-enrolment. The study involved 168 randomly selected households in 16 districts and four refugee-hosting areas.

Around 81% of the households reported lack of money as the reason why their children dropped out of school, while 58% said the same factor compelled them to not enrol their children in school.

This is backed by the 2015 study by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) which says poverty remains one of the biggest barriers to children reaching their full potential. It adds that more than half of Uganda’s children are living in poverty, which deprives them of things like education.

Child labour

Other factors cited for school dropout, according to the study led by Mbabazi, include children’s involvement in domestic work, long distances to school, children’s obligations to the family business and farm, children’s lack of interest in education and overcrowding in schools.

However, certain factors contribute to dropout at varying levels in different regions, according to the study, which was endorsed by Government and development partners.

For instance, a substantial number of households in the eastern region listed working on the family farm or business as a reason why children drop out of school, while the northern region had the lowest number of households citing the same reason for leaving school.

Karamoja had the lowest number of respondents who cited children’s lack of interest in school as the main reason for dropping out while many families in northern Uganda listed it as a major contributor.

Hidden costs

Although UPE is free, the study notes that fees for uniforms, scholastic materials, exams and development funds continue to affect the most disadvantaged, leading to school dropout.

The 2015 study by UNICEF adds that many families cannot raise such fees due to poverty. It also cites teacher absenteeism and poor quality of teaching in public schools, violence in schools, and limited sanitary facilities, among factors responsible for the dropout.

Sandra Kisitu a teacher in Mayuge district said increasing access to sanitary products like pads could keep many girls in school.

A 2018 study led by Douglas Candia, an assistant lecturer in the department of planning and applied statistics at Makerere University, cites the characteristics of the individual learners and parents, household structure and community among the non-school factors responsible for dropout.

The study, which was published in the People: International Journal of Social Sciences, says the likelihood of a child dropping out of school in Uganda increases with age and reduces with the increase in years of preschool attendance and the household head’s level of education.

It adds that children with special needs are more likely to drop out of school than other children due to the lack of facilities in schools to allow them to thrive. The absence of two biological parents of the child in a household is also cited among the causes of school dropout.

Preprimary education

According to Mary Goretti Nakabugo, the executive director of UWEZO Uganda, an organisation which researches education, many children who join primary are unprepared for school due to the absence of pre-primary education.

Public primary schools in Uganda do not offer preprimary education. It is provided by private players and the majority of the kindergartens are located in urban areas – targeting parents in towns who have the means to pay for this type of education.

Yet over 70% of the ten million children said to be in primary schools now study in UPE schools which are concentrated in rural areas.

“By the time the children who have gone through preprimary reach primary, they are ready for school and it is easy for them to acquire foundational skills which include reading and writing,” Nakabugo said. “It is easy for such students to learn and meet the expectations of primary education,”

She adds that the children who do not receive preprimary education leave Primary One without these foundational skills – a problem which gets carried to other classes.

“The automatic promotion policy pushes these problems to other classes,” Nakabugo says. “With time, the children get frustrated and drop out,”

For several years, players in the education space like Nakabugo have asked Government, which is still not funding UPE adequately, to set up preprimary institutions.

The Government has remained noncommittal on this proposal which would require billions of money to implement per year.

Vocational training

Shannon Kakungulu, a medic, asked the Government to promote vocational education to absorb the children who have dropped out. These institutions, he said, will give these children skills to contribute to the country’s industrialisation drive.

Badru Ssenoga, the head teacher of Kibuli Demonstration School, said there is a need to fight early marriages, which is one of the causes of school dropout. Robert Wamimbi a head teacher of Tower Primary School in Mbale district asked the Government to fight child labour.

The education ministry plans to roll out next term a nationwide tracking system called Teacher Effectiveness and Learner Achievement (TELA) to monitor teacher and learner school attendance. The head of the directorate of education standards in the ministry, Frances Atima, said this innovation will promote effectiveness among teachers and encourage children to remain in school.

Under the Presidential Industrial Hubs, various regional skilling centres have been set to train all interested Ugandans, including those without formal education, in various vocational fields such as carpentry, hairdressing, tailoring, shoe making, bakery, confectionery and welding.

The regional skilling centres, offering six-month free residential training, have so far been set up in Gulu, Lira, Mbarara, Kasese, Kyenjojo, Mubende and Kayunga. Others are located in Mbale, Napak, Kween, Masindi, Zombo, Soroti, Kibuku, Adjumani, Ntoroko, Kabale, Masaka and Jinja. So far, 2,600 youth have graduated from these training centres, which were set up last year.

How to stem school dropout

– Eliminate all schooling costs

– Eliminate violence and discrimination

– Invest in teacher training

– Implement special needs education policy

– Support pregnant girls and teen mothers to stay in school

– Strengthen vocational and technical training

– Implement Uganda-integrated early child development policy

– Implement laws and policies against child labour

– Emphasize poverty eradication

– Recruit more teachers and motivate them

– Train local leaders on educational issues

– Consider placing nurses in schools

– Educate parents on the value of education

– Track children who have dropped out

– Improve school environment

– Build more schools

– Improve household-level food security

– Promote extracurricular activities at school

– Promote mandatory preprimary education

– Curb absenteeism

Source: Out-of-school children study in Uganda study 2014, Situation analysis of children in Uganda report 2014 and People: International Journal of Social Sciences

Leave feedback about this